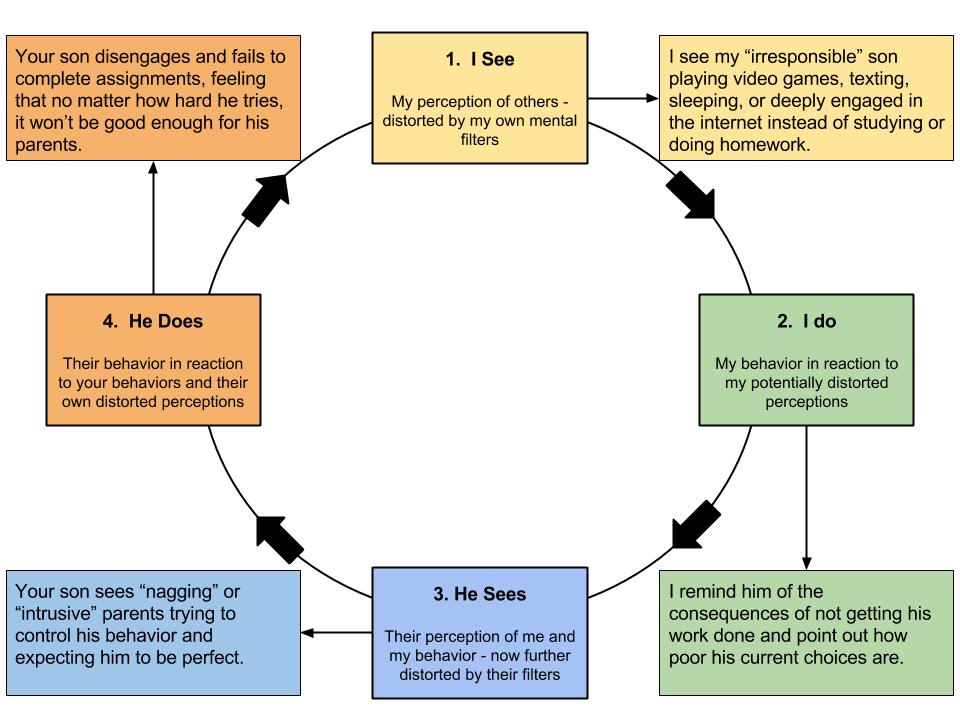

Video games are available everywhere – they are more accessible than they’ve ever been. Console gaming systems (i.e., PlayStation, Xbox), online adventures (World of Warcraft), and mobile games provide nonstop opportunities to be plugged-in. Unfortunately, pursuing those opportunities may mean failing to meet responsibilities, ignoring relationships, and losing sleep. Those issues can result in some serious consequences. Gaming isn’t all bad, and it can have some benefits, but only when it’s used in a healthy way.

Much like other potentially addictive behaviors, moderation the key to healthy gaming. With children and adolescence, parents become responsible for setting concrete limits and boundaries to ensure that moderation.

Here are some recommendations for health-conscious parents of gamers:

1) Use video game time as a reward and in small quantities. For example, “You did all your chores, go ahead and play this age appropriate game for 30 minutes.”

2) Learn about the games your kids are playing. How do you know what’s appropriate? Do the legwork necessary to find out. You can read about games and apps at Common Sense Media to learn about the content and what other parents (and kids) think about the games your child has access to.

3) Plan “gaming time” in a way that it doesn’t compromise good sleep hygiene. If your child is losing sleep to play a game, it has already become problematic. Perhaps they have time in the morning once they’re ready for school or after they’ve completed homework in the evening.

4) Do not use video games as a babysitter. It becomes increasingly problematic for parents to monitor and regulate video game use if they depend on the activity for “supervision.”

5) Provide a space in a common area for children and teens to access the games they want to play (console, phone, or computer). Do not allow games to be played in their room; it becomes difficult to limit playing time, frequently results in compromised sleep, and reduces barriers to inappropriate content.

6) Avoid games with no distinct end such as World of Warcraft or many of the online first person shooters. Taking a few seconds to read the description from Common Sense Media, parents will learn that World of Warcraft contains, “…endless exploration and no clearly defined levels”and will necessitate external boundaries.

7) Define limits based on time. When limits are set by an “in-game” construct (i.e. beating a boss, leveling up, or finishing a chapter) this may be the start of problematic video game play.

8) Be aware that individuals that suffer from ADHD have a higher addiction potential, especially boys, and require particularly close monitoring to ensure healthy gaming behaviors.

*Special thanks to Dr. Anatol Tolchinsky for his insight and expertise in relation to maladaptive video game play. He was generous enough to share the framework of these guidelines out of the goodness of his heart.