I revisited the book Mindset by Carol S. Dweck, Ph.D. I dove in, took notes, and highlighted the big ideas and inspiring quotes. While I won’t rehash the entire book here, I’ll share some of the key concepts.

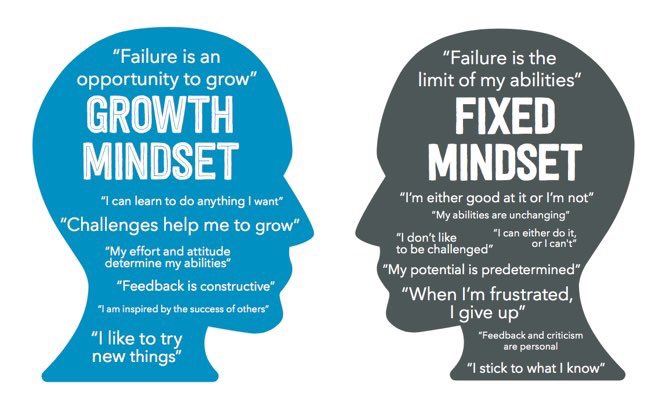

Dr. Dweck’s book is built on an exploration of fundamental differences in mindset – fixed mindset vs. growth mindset. In the fixed mindset people view skills and abilities as static, as in unchanging. It’s easy to come up with examples of the fixed mindset if you complete the sentence “I’m just not good at ________.” People fall into the fixed mindset with all sorts of things. As I read the book, I couldn’t help but hear echos of my self-assessments. “I’m just not musical.” “I just don’t have good hand-eye coordination.” “I just don’t have an eye for design.” I could go on, but I’ll spare you more examples of my self-proclaimed shortcomings. Fixed mindset can also apply to talents when we complete sentences like “I’ve just always been good at __________.”

Either way, the fixed mindset sets us up for failure on a grander scale than any particular skill or ability. By clinging to a fixed mindset, I effectively eliminate my willingness and ability to improve myself in any way. Every shortcoming becomes a lifetime sentence of mediocrity. Anytime I try something new and I’m not good at it, my fixed mindset tells me I have a fundamental deficiency in that area….and I can’t really do anything about it. Ouch!

The fixed mindset, as you might imagine, leads to avoiding anything that challenges self-perceived strengths. For example, If my fixed mind tells me I’m good at writing, I’m only going to write in situations where I’m virtually guaranteed to be affirmed and validated. If critical feedback comes my way, it may pop my ‘good writer’ bubble, and if I’m not inherently good, I’ll never be good. When the fixed mind is forced to face critical feedback, it justifies and blames in order to protect the perception of ‘natural’ ability. This avoidance of challenges and useful feedback actually creates stagnation and strengthens the notion of static abilities.

Growth mindset, as you might imagine, focuses on our incredible capacity to learn new things and develop new skills. Individuals embracing a growth mindset seek out opportunities to learn from feedback – they don’t fear failure because they believe any lack of success is temporary and dependent solely on commitment and effort.

Want to see where you apply your own growth mindset? Complete the sentence, “After a lot of hard work, I learned how to __________.” Any time you’re willing to start with the basics and build from there. Growth mindset generally requires patience, openness to feedback, a willingness to be ‘unsuccessful’, and the ability to enjoy the process of improving. When you can feel pride based on individual growth rather than comparative success or narrowly defined outcomes, you’re in the growth mindset.

The growth mindset allows us to pursue literally anything and everything regardless of our current skill level. It opens the door to any and every experience. It ignores any of the standard excuses, turning “I’m too old” into “It’s never too late.” “I’ve never been good at that.” becomes “It’s going to be so fun to learn how to do this.” The best part about all of this is the fact that growth is virtually guaranteed if you can sustain this mindset throughout the process.

Because so much of our mindset is based exclusively on the internal dialogue between our ears, it’s tough to create a concrete plan for shifting from fixed to growth. That won’t stop us from trying though. The first step is committing to cultivating the growth mindset, intentionally replacing unhelpful thoughts with thoughts of growth. Use the examples below, and feel free to come up with your own.

Every failure is an opportunity to learn.

Feedback only helps me learn and grow.

Everything I’ve ever done has required effort to get better.

I can get better at anything I work at.

If I’m willing to looking at my ability honestly, and celebrate small successes, I can have fun regardless of outcomes.

The how matters more than the what.

Take a new challenge, practice the growth mindset, and let us know how it goes.

If you’d like to hear more of Dr. Poinsett’s thoughts on Mindset, you can listen to his discussion of the book on The Victory and The Struggle Podcast.